Sharon Zukin's book

Point Of Purchase: How Shopping Changed American Culture has an interesting chapter that follows a New Yorker, Cindy, on her quest for "the perfect pair of leather pants". "Leather is such a classic thing," says Cindy.

Wait, what? Not when we are talking about pants! Zukin seems to agree with me... at first. She writes:

When I was her age, in my late twenties, I never thought that leather pants were classical. In those years, if you wore leather pants, especially black pants, people thought you were some sort of a sexual fetishist — or, at the very least, that you didn't mind being stared at for flaunting a well-honed pair of thighs. Recently, however, leather pants have changed their image. If you wear them with a cashmere turtleneck and a houndstooth jacket, they look simple, rich, and casual. They represent the 'classic' American sense of comfort with a materially satisfying life. (89-90)

My first reaction was to check when this book was written – like, 1985 or something? But no. It was published in 2005. Perhaps it's an American thing, or perhaps it's Cindy's own taste; after all, she rejects some leather hipster flares she sees at

The Gap because she's obsessed with finding "classic" (ie, high-waisted, straight-legged) pants.

Still, leather pants are semiotically very different from a leather jacket. While the jacket is an outer garment, a carapace, the pants are usually tight and worn next to the skin, becoming a mimetic 'second skin'. The fact that they hug the crotch, and the fact that you can't launder them frequently, like other types of pants, marries unfortunately with the animalistic connotations of leather in general to make one think, basically, that leather pants are for dirty sluts.

PVC is something else again. Plastic-look leggings like the ones

Kate Moss wore at Glastonbury

last year are currently "on the radar" in Australia, according to the May 18 issue of

The Sunday Age's M magazine. Honestly, I roll my eyes. Also I feel sorry for

Josh Goot, whose

Designers For Target range was all over this trend last year, with black foil leggings for $70. It irritates me that

Target don't archive their previous Designers on the

website; it's as though they vanish into thin air. Poor old Josh would know that's not true – his stuff seemed to hang around in the stores forever, gradually getting cheaper and cheaper. (The leggings went down to $14, according to the ever-alert

Vogue Forums.)

The mainstreaming of this style means we'll see

more people wearing them this winter; some hipsters were wearing them last winter as an edgier take on matt black leggings. My theory about this is that if you wear a lot of black and monochrome, like plenty of art and fashion hipsters do, you use texture to spice things up: shiny Lycra,

American Apparel style; 'wet-look' textures; lamé and lurex.

But let's get back to that 'edgy' stuff. Thanks to

Vivienne Westwood's SEX boutique and its punk associations, PVC now connotes both fetish and rock. For me it also connotes goth, of that particularly unpleasant 'techno-goth' strain – and that's something that I think differentiates PVC from leather. Yesterday I was reading a great book called

Wild: Fashion Untamed that was basically the catalogue for an exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art. Over various themed and gloriously illustrated chapters it examines fashion's use of leather, fur, feathers and other animal motifs.

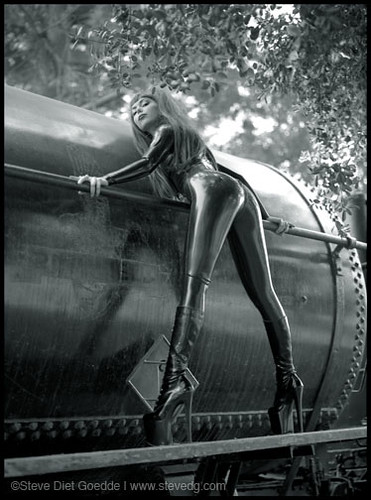

So I was examining a photo spread that juxtaposed

Diana Rigg in her black leather Emma Peel jumpsuit from

The Avengers with a photo of the dominatrix and latex fashion designer

Pigalle in a catsuit of her own design. I was curious about what made the leather different from the latex. These are the actual two images in the book: I'm quite pleased I could find them online.

While it's common to speak of

Rigg as being in "skin-tight" leather, it fits relatively loosely in the arms and across the torso. And the arms are too short! It looks absurdly modest next to the moulded, almost Batsuit-esque PVC outfit worn by

Uma Thurman as Emma Peel in the awful and unnecessary movie remake.

Although it doesn't cling to the body like the synthetics, the leather is still inescapably made from animal skin. It's organic, tough,

supple – we can't really speak of synthetics being 'supple'. It reminds me of the way a lion's skin slides over its shoulder blades as it prowls, and then slackens in repose: you can imagine the way that the leather will tauten and slacken as Emma Peel kicks arse.

By contrast, the latex is almost terrifyingly, surreally robotic and futuristic.

Pigalle's haunches look like pistons in a machine, or even like the liquid metal from which the T-1000 cyborg in

Terminator 2: Judgment Day is constructed. The suit appears absolutely seamless, almost erasing the reality of the body beneath: it seems impenetrable, despite the sexual invitation of her pose.

The same inorganic, anodyne quality attends the PVC leggings that are in fashion at the moment. Various commentators nodded approvingly at

Kate Moss's decision to wear something she could "wipe clean" to Glastonbury. (Because of the mud, smutties!) As the look trickles down, it seems to say something vaguer along the same lines: about looking 'sharp', 'clean', 'crisp' or suchlike.