At the start of December I went to the CSAA conference in Canberra. One of the highlights for me was the fashion stream. I had decided not to participate because I was afraid that it would be ghettoised - it was referred to as a "fashion workshop" and I was worried that it would just be a bunch of self-identified 'fashion researchers' speaking to each other's papers, rather than forming a dialogue with the other delegates. As it turned out, the fashion papers were all held in the same lecture theatre but simply formed one of the parallel sessions, so I needn't have worried.

Many of them were frustrating because they were expository rather than analytical. They set out to describe a particular phenomenon, which many of them did in a lively and entertaining way, kind of like an interesting TV documentary. But some papers spent too much time introducing the material and not enough time situating it in a theoretical or social context. And some presenters didn't seem to have asked themselves, "What are the larger ramifications of my topic? What's at stake here?"

But one of the most exciting papers I saw was Miriam Silvester's, which focused on how strategies of customisation can extend the life of a garment beyond the traditional consumer logic of 'fast fashion'. Indeed, she spoke of the "rhythms" of clothing. Silvester is a Wellington-based designer and researcher, and a lovely person to boot. It was truly a pleasure to meet her. Perhaps it's my own impetus towards keeping lists and delineating categories, but I love the way she keeps a visual diary of all her clothes, tracking the time, energy and money she's spent on maintaining them.

Indeed, what I really liked about Silvester's research is the way that customisation isn't presented as a purely stylistic gesture or as mark of singularity for its own sake. Instead, it is a pragmatic acknowledgement of the relationships that people form with their clothing, and the way those relationships change over time. For example, you might have a favourite windcheater that you want to salvage even when it becomes torn or stained; or you might get bored with it, but it's too good to throw away. Silvester is interested in how these processes of salvage are entwined with the creativity expressed through customisation.

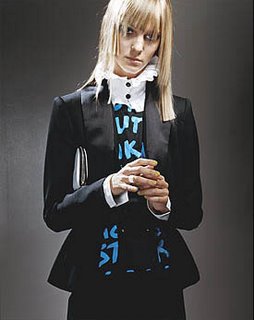

Look at that; isn't it beautiful the way the damaged cuffs are reworked into a design feature? For a major project, Silvester designed garments that actually anticipate and incorporate their own ruin. Her "Spill" range contains drawstrings that can be pulled to create ruched sections that disguise tea, wine or cigarette marks.

For me this seems the very opposite of those pre-distressed garments you can buy new in shops, which, ironically, by employing signifiers of 'use' and 'customisation', actually lock users out of the opportunity to form their own relationships with the garments. That is, they deter customisation.

Silvester sketched a useful model of clothing rhythms (the speed at which garments are replaced) and what she called "fashion levels" (the degree to which people respond to trends). People with low levels of fashionability, who buy purely for utility, and those with high fashionability, who can make current trends work with the minimum of new purchases, both have sustainable consuming practices. It's those with medium fashionability who are the worst consumers, because they buy and quickly discard garments in order to stay 'in fashion'. (And, I'd add, the pre-distressed garments are largely targeted to this segment.)

This begs the question of whether fashionability can be taught, and whether it even ought to be. I mean, who am I, or anyone else, to assume a position of expert knowledge and impose on other people my own ways of placing myself within current trends? All the same, there are many ways to teach people how to be fashionable - magazines, copying celebrities, observing people in the street, and the 'styling tips' that so many retail chains provide via their catalogues, their visual merchandising and their staff. I'm interested in this, and I'll return to it.

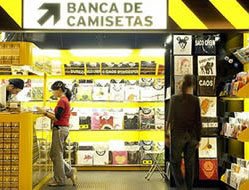

But Silvester has come up with a really interesting experiment in encouraging people to customise. It's called Wellytown. Silvester produced a lovely line art illustration of a Wellington streetscape as seen from Mt Victoria. She printed this on t-shirts which she distributed to friends and acquaintances, telling them they were free to customise the t-shirt however they liked - drawing, painting, embroidering, appliquing, etc. Some of the results were really beautiful. She's also begun selling the t-shirts in stores, together with art materials and some basic suggestions for customising. And she encourages people to photograph their work and send it to the site.

That last idea really excites me. It's as if the t-shirts are a way to join a community of creatively engaged Wellingtonians. It's a club whose members recognise each other, not only by the original image, but also by the singular ways in which they've adapted that image. It's a really smart idea. Silvester has also produced Wellytown posters which, hopefully, will lead people to the site and expand the communal idea into virtual space. There are so many wonderful possibilities.

What really interested me is that Silvester found many participants in her initial project were afraid of 'ruining' their t-shirt. Her theory is that this is because the garment is worn close to the body (as opposed to people not worrying so much about altering a collaborative artwork, for instance). But this tells me that there's a fine line between successful and unsuccessful customisation. Perhaps it's about the process - you don't quite know what the results will be until you've arrived at them, and this uncertainty deters you from even beginning. Or perhaps it's about the finish - you have an uncompromisable vision of what you want the garment to look like, and you're worried that you don't have the skills to produce this vision so you'd rather leave it to 'professionals'.